Given the news of the passing of Terry Jones, it seems appropriate to kick things off with one of my favourite parts of any Monty Python film:

Specifically:

ARTHUR: Who lives in that castle?

WOMAN: No one lives there.

ARTHUR: Then who is your lord?

WOMAN: We don’t have a lord.

ARTHUR: What?

DENNIS: I told you. We’re an anarcho-syndicalist commune. We take it in turns to act as a sort of executive officer for the week.

ARTHUR: Yes.

DENNIS: But all the decisions of that officer have to be ratified at a special biweekly meeting.

ARTHUR: Yes, I see.

DENNIS: By a simple majority in the case of purely internal affairs,–

ARTHUR: Be quiet!

DENNIS: –but by a two-thirds majority in the case of more–

ARTHUR: Be quiet! I order you to be quiet!

WOMAN: Order, eh — who does he think he is?

ARTHUR: I am your king!

WOMAN: Well, I didn’t vote for you.

ARTHUR: You don’t vote for kings.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail: Peasant Scene

Recently, I’ve become really interested in how decisions are made. Not personal decisions, such as “shall I change career?” or “who should I marry?”, but organisational decisions, such as “which project management tool should we use?” or “what should our strategy for the next three years be?”

As useful as they can be elsewhere in life, for this, things like The Decision Book don’t really cut it here. What we need is an approach or matrix; a way of deciding how, going into the situation, decisions are going to be made.

Related to this, I think, is the “default operating system” of hierarchy. I’ve cited elsewhere Richard D. Bartlett talking about the bad parts of hierarchy as being ultimately about what he calls “coercive power relationships”. In a hierarchy, people towards the bottom of the pyramid are being paid by the person (or people) at the top of the pyramid, so what they say, goes.

This means that, within a hierarchy, you’ve got a structure for the decision-making process, with power relationships between participants. And then, ultimately, however democratic the process purports to be, it’s ultimately the Highest Paid Person’s Opinion (HiPPO) that counts.

But what about in other situations, where the decision-making structure hasn’t been created? Who decides then?

For me, this isn’t an idle, theoretical question. I’ve seen the problems it can cause, especially around inaction. You can get so far by meeting up and having a big old discussion, but then how to you come to a binding decision? It’s tricky.

With non-hierarchical forms of organising, even getting into the decision-making process requires two things to happen first:

- Codification of power relationships

- Agreement as to how a binding decision can be made by the group

Let’s consider a fictional, but relatable, example. Imagine there’s a group of parents who have voluntarily decided to come together to raise money for their childrens’ sports team. They are not forming a company, non-profit, charity or any other form of organisation. They do not operate within a hierarchy. Nor have they decided how binding decisions can be made by the group.

Now let us imagine that this group of parents has to decide how best to raise money for the sports team. And once they’ve done that, they have to decide what to spend the money on. How do those decisions get made? What kinds of approaches work?

It is, of course, an absolute minefield, and perhaps why volunteering for these kind of roles seems to be on the decline. These situations can be particularly stressful without guidance or some kind of logical approach to non-hierarchical organising.

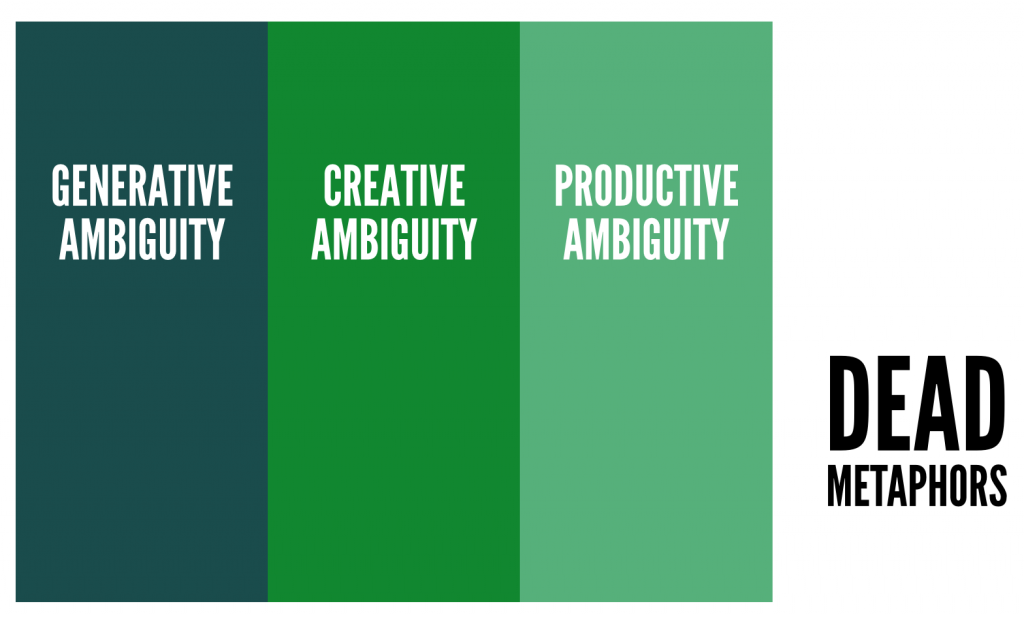

What has this got to do with ambiguity, and more specifically, the continuum of ambiguity shown above? I’d suggest that what is required in our fictional example is a way of organising that strikes a balance. In other words, one that that is Productively Ambiguous.

Hierarchies are a form of organising that can work well in many situations. For example, high-stakes situations, times when execution is more important than thought, and the military. For everything else, hierarchical organising can be a dead metaphor. It doesn’t represent how things are on the ground, and doesn’t allow any productive work to happen.

Imagine the situation if that volunteer group of parents decided to organise into a hierarchy. I should imagine they would spend more time thinking about and discussing power relationships and status than they would doing the work they’ve come together to achieve.

To the left of Productive Ambiguity lies creative ambiguity:

Whilst a level of consensus can exist within a given community within this Creative ambiguity part of the continuum, it nevertheless remains highly contextual. It is dependent, to a great extent, upon what is left unsaid – especially upon the unspoken assumptions about the “subsidiary complexities” that exist at the level of impression. The unknown element in the ambiguity (for example, time, area, or context) means that the term cannot ordinarily yet be operationalised within contexts other than communities who share prior understandings and unspoken assumptions.

Digital literacy, digital natives, and the continuum of ambiguity

Creative ambiguity relies on unspoken assumptions and previous tight bonds between people. This approach might work extremely well if, for example, the parents had themselves been part of a sports team together in their youth.

The chances are, however, that there would be at least a minority in the group who do not share this commonality. As a result, those unspoken assumptions would become a stumbling block and a barrier.

Far better, then, to focus on the area of productive ambiguity:

Terms within the Productive part of the ambiguity continuum have a stronger denotative element than in the Creative and Generative phases. Stability is achieved through alignment, often due to the pronouncement of an authoritative voice or outlet. This can take the form of a well-respected individual in a given field, government policy, or mass-media convergence on the meaning of a term. Such alignment allows a greater level of specificity, with rules, laws, formal processes and guidelines created as a result of the term’s operationalisation. Movement through the whole continuum is akin to a substance moving through the states of gas, liquid and solid. Generative ambiguity is akin to the ‘gaseous‘ phase, whilst Creative ambiguity is more of a ‘liquid‘ phase. The move to the ‘solid’ phase of Productive ambiguity comes through a process akin to a liquid ‘setting’.

Digital literacy, digital natives, and the continuum of ambiguity

Instead of hierarchy or unspoken assumptions, progress happens by following a path between over-specifying the approach, and allowing chaos to ensue.

In practice, this often happens by one or a small number of people exerting moral authority on the group. This occurs through, for example:

- Successfully having done this kind of thing before

- Being very organised and diligent

- Having the kind of personality that put everyone at ease

I have more to write on all of this at some point in the future, but I will leave it here for now. It’s interesting that this is at odds with the way that I see many attempts at decision-making happen – either inside or outside organisations…