Over at the WAO blog, I’ve published a post about ambiguity and how it can be applied in work contexts.

You can access the post here.

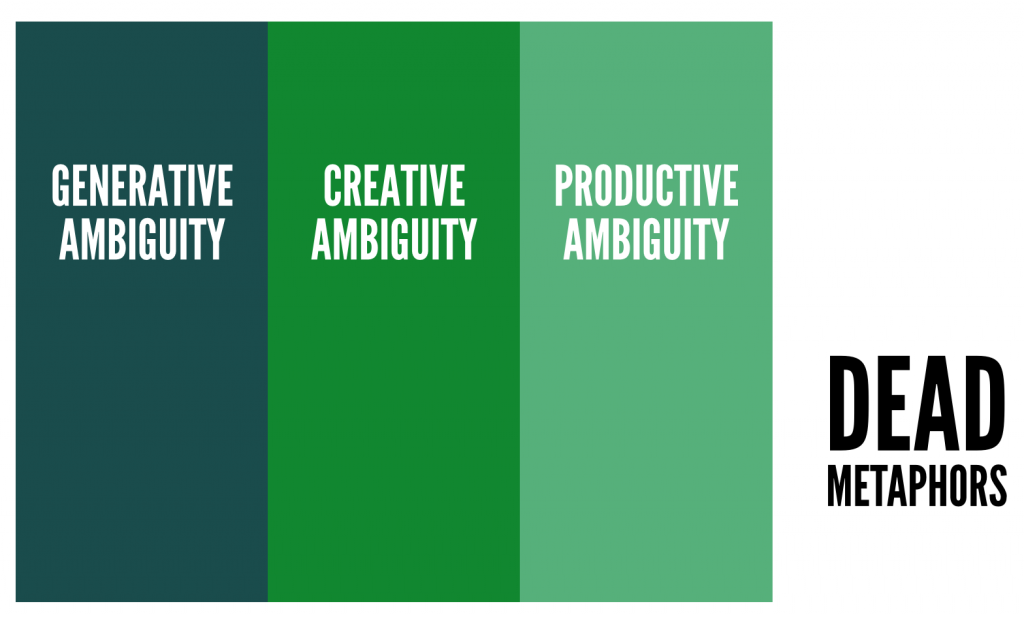

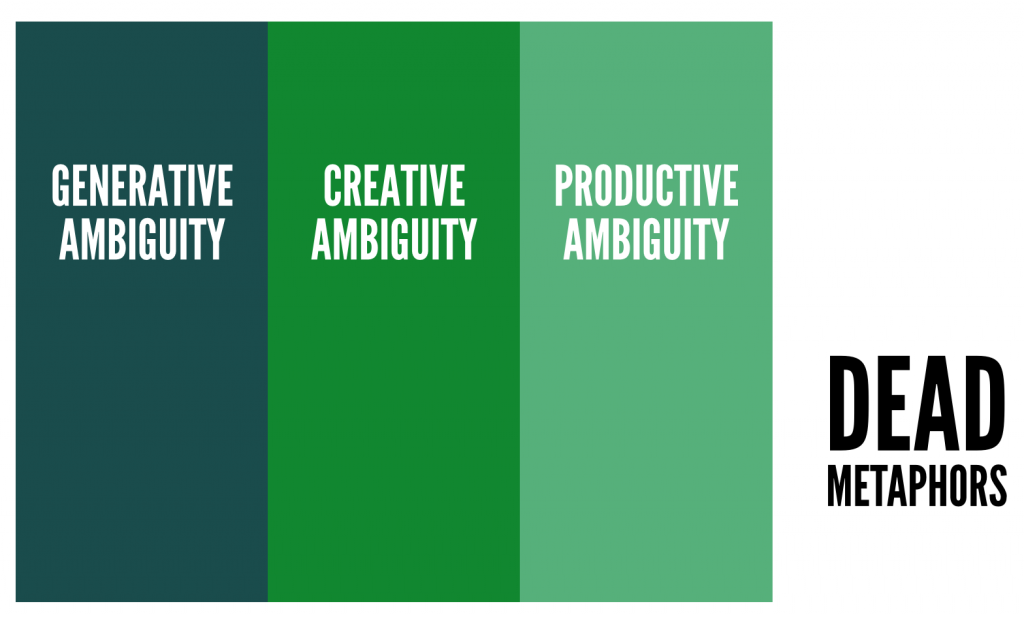

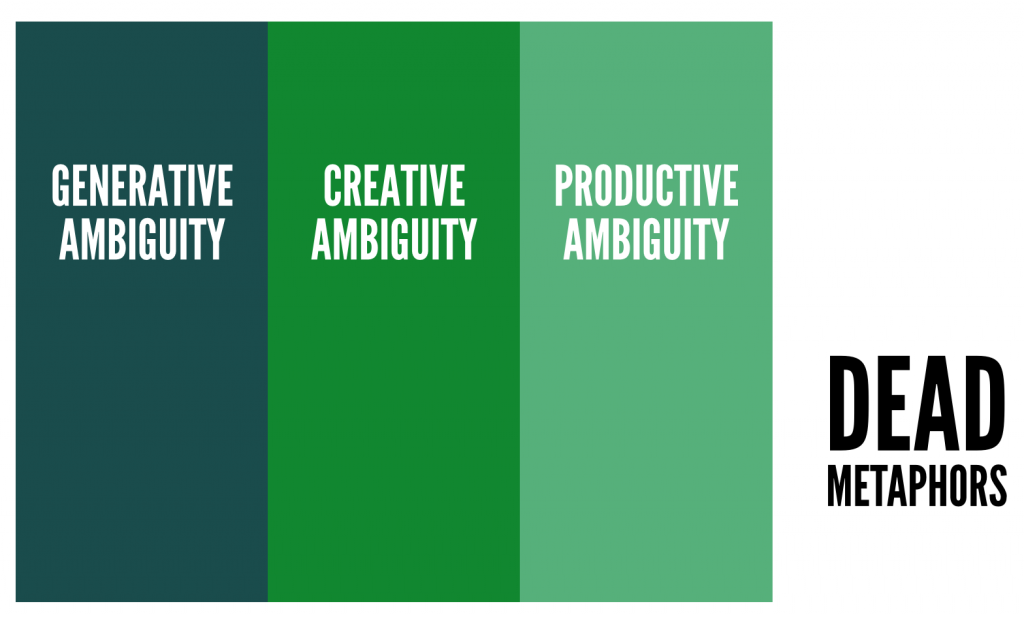

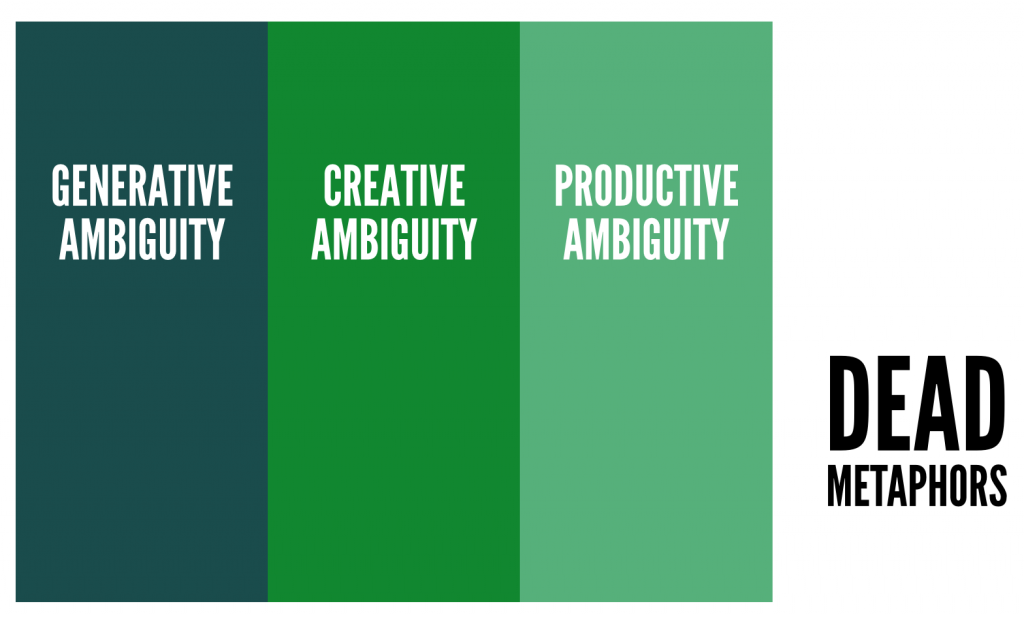

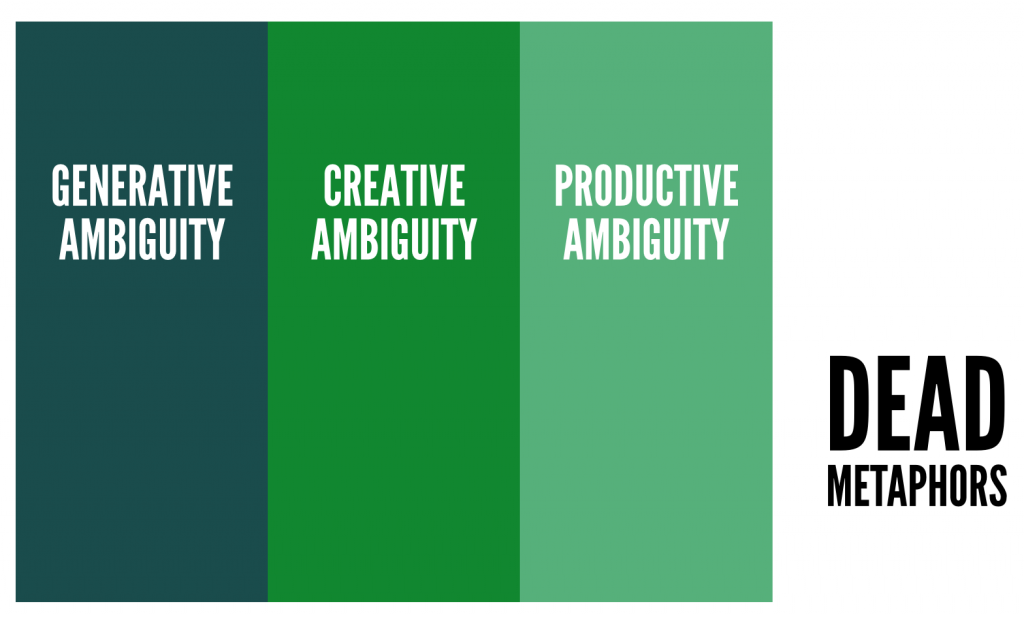

Introducing a continuum of ambiguity and reflecting on importance of avoiding dead metaphors in the workplace.

Over at the WAO blog, I’ve published a post about ambiguity and how it can be applied in work contexts.

You can access the post here.

After all, the most basic form of recognition is: “I see you.”

When most people think about earning a badge for something, they think about being recognised for that thing. This is correct: badges do in fact signify recognition.

However, most badges are issued for a subset of recognition practices, namely to indicate that something is in some way ‘valid’. For example:

Badges of this type are useful, particularly when thinking about people who are in transition. This usually happens when people are looking to land first job, being promoted at work, or looking to move on in their career.

To use my continuum of ambiguity, we can say that validity badges are ‘productively ambiguous’. That is to say that most people looking at the badge and its associated metadata will understand what it is for and how it is useful.

Further to the right, and off the end of the continuum is the danger zone of ‘dead metaphors’. In this context, that would apply to badges that validate skills we expect everyone to have.

I want to talk about badges for recognition which fall in the other two parts of the continuum: generative ambiguity and creative ambiguity. After all, we don’t only engage in recognition practices to validate other people’s skills.

Sometimes we recognise things such as:

In fact, sometimes it’s enough just to recognise somebody or some thing’s existence.

One dictionary definition I came across, among the many I looked at in preparation for this post, defined recognition as being an ‘uncountable noun’. In other words, recognition is a quantity which is measured in an undifferentiated unit, rather than being something which can be divided into discrete elements.

Let’s return to the two parts of the continuum of ambiguity that I want to discuss in relation to badges:

In my work on digital literacies, I often talk about power dynamics that are at play when people come up with definitions. By naming things we attempt to exert power. There is nothing inherently wrong with this, and productive ambiguity is how we get things done at scale.

But focusing on scale isn’t always useful. Our relationships with family, friends, and community members don’t always scale. This is why there’s been so much discussion of Dunbar’s Number over the last 10 years. There may well be a ‘cognitive limit’ to the number of people with whom we can maintain stable social relationships.

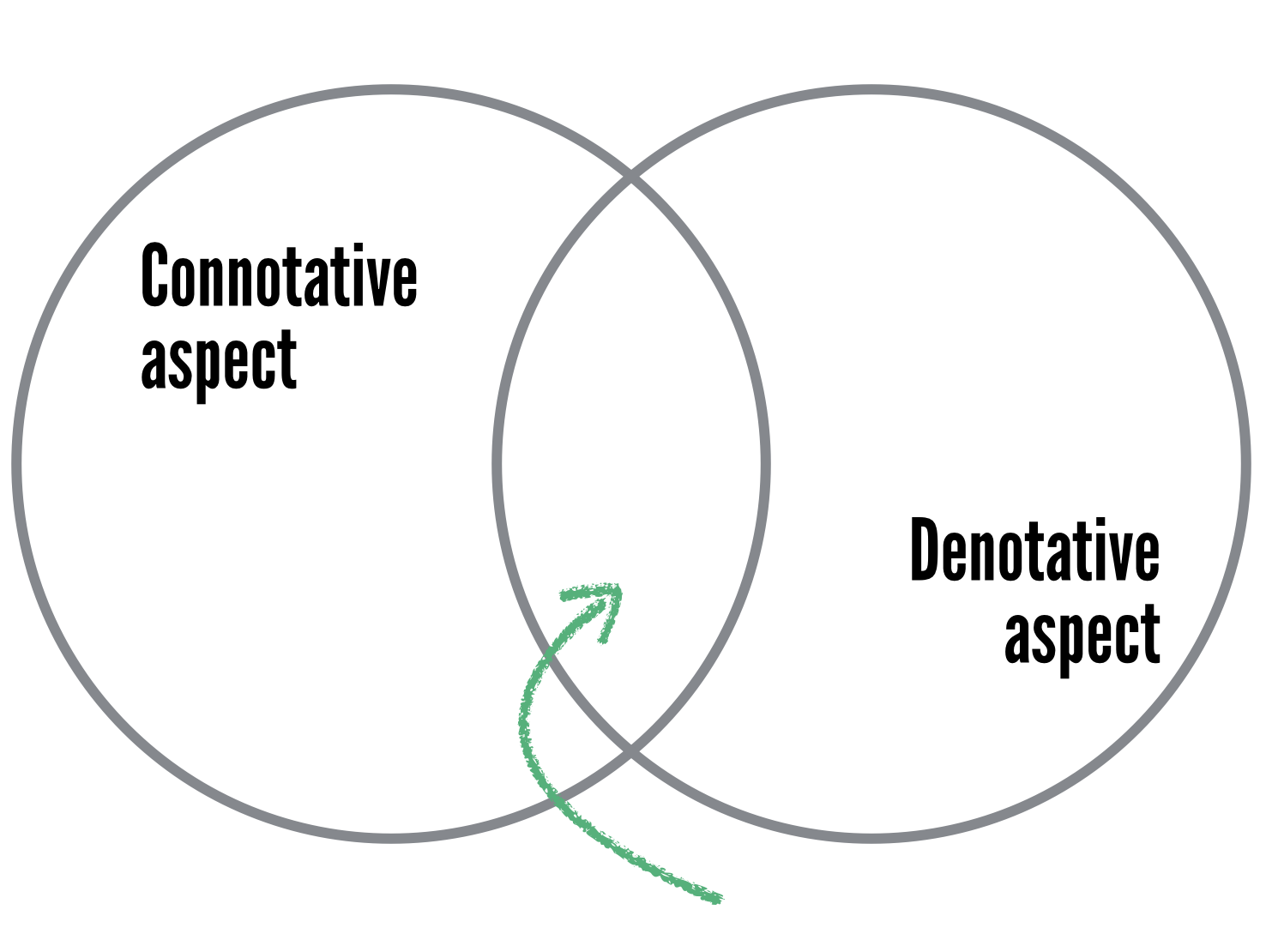

The continuum of ambiguity exists at the overlap of the connotative and denotative aspect of the words we use to convey meaning. If something denotes something else then it ‘stands’ for it. If something connotes something else then it is indicative of it.

The same is true of badges for recognition practices. Instead of only leaning towards ever more denotative badges, I want to suggest that we leave room for badges that connote relationships, potential, aspiration, and even existence. After all, the most basic form of recognition is: “I see you.”

A reminder to myself to be aware of the power of ambiguity within my own work and of the different forms it can take.

Ambiguity can often be caused through intentional or intentional use of zeugma and syllepsis:

In rhetoric, zeugma (/ˈzjuːɡmə/ (listen); from the Ancient Greek ζεῦγμα, zeûgma, lit. “a yoking together”[1]) and syllepsis (/sɪˈlɛpsɪs/; from the Ancient Greek σύλληψις, sullēpsis, lit. “a taking together”) are figures of speech in which a single phrase or word joins different parts of a sentence.

In my doctoral thesis, I noted that the words ‘digital’ and ‘literacy’ were combined to produce different kinds of ambiguity:

Zeugmas are figures of speech that join two or more parts of a sentence into a single noun, such as ‘digital literacy’. It is unclear here whether the emphasis is upon the ‘digital’ (and therefore an example of a prozeugma) or upon the ‘literacy’ (and therefore a hypozeugma). Which is the adjective?

Once you’ve spotted your first zeugma, you see them everywhere. They can be used to enlighten but also to deceive. I’m often a fan: terms where two words are ‘yoked together’ can be incredibly productive, leading to breakthroughs in groups that would otherwise be directionless.

The way this approach works is to play around with the boundary of what something denotes (i.e. represents) and what it connotes (i.e. implies).

Within this overlap are different types of ambiguity, which I usually represent with the continuum of ambiguity (below). This is explained in more detail within a paper I wrote with my thesis supervisor, but broadly speaking:

What’s interesting in my work is that I get to collaborate with quite a few different organisations, either as clients or as sister organisations working towards a shared goal.

There have been some interesting zeugmas that arise and do some important work at the level of Creative Ambiguity and Productive Ambiguity. For example: Cooperative Technologists [CoTech] where it’s often unclear as to whether we’re cooperative technologists or cooperative technologists. Is the emphasis on the former or the latter?

My experience is that while zeugmas open up space for productive discussion and action, the terms themselves are usually on a journey. They may move in a linear way from Generative through Creative, to Productive Ambiguity before becoming a Dead Metaphor. But more often, they oscillate between Creative Ambiguity and Productive Ambiguity, with the terms being reinvigorated every so often with new insights and impetus.

In general, this post on a oft-neglected blog is mostly a reminder to myself to be aware of the power of ambiguity within my own work and of the different forms it can take.

Vagueness is, of course, always to be avoided (and sits to the left of Generative Ambiguity) but it’s actually quite a rare thing in my world.

A story using characters to represent different parts of the continuum of ambiguity.

Imagine the situation: there’s a business meeting. I’ll leave it up to you as to whether this is an in-person meeting or a virtual one, but there are five people present:

These are all supposed to represent various parts of a continuum that I’ve used a lot on this blog. In fact, I’ve used this image in pretty much every post. However, what it doesn’t include is the area to the left of the continuum — thoughts, ideas, and utterances that are ‘vague’.

Back to the meeting, and Dave is speaking in clichés (aka ‘dead metaphors’) again. “What we need to do is synergise our verticals” he says. Parvati rolls her eyes; Dave’s been spending too much time on LinkedIn.

“Dave, I don’t think you understand our strategic business direction” says Vera. “We’re aiming to integrate new technologies to enable growth!” Everyone nods their heads, but no-one really understands what she means by this. “Have you got any ideas, Gerald?”

Looking uneasily around the room, Gerald utters a nervous little cough before saying, “well, I did have one idea, but I’m not sure if it’ll make much sense to you.” He looks out of the window, inhales deeply, and then spends the next few minutes outlining how he believes that web3 is like a cross between the Roman empire and freeform jazz. The rest of the meeting’s participants are utterly lost but try not to show it.

After a few awkward seconds of silence, Chitundu raises a finger and starts talking about a conference he went to recently. “At BizFest last year there was a speaker who was talking about the application of blockchain to verify core business processes,” he says. “What I liked about it was that he was really practical, but I can’t exactly remember what I thought we could use it for.”

Dave and Gerald are no longer concentrating and are instead checking their emails, but Vera chips in. “Yes, this is what I meant about integrating new technologies to enable growth!” Emboldened, Chitundu continues, “well you know how in the last annual report it showed we spend a lot of money on de-duplicating records? Perhaps we could use it for something to do with that?”

Suddenly, Pravati is drawing shapes connected with lines on a whiteboard. “Yes! She says, blockchain is basically a boring, back-office technology. So as long as we don’t store any sensitive data on there, we could use it to streamline our verification processes.” Vera’s eyes have glazed over slightly but she’s nodding.

Chitundu is excited. “I love this, and I think we should perhaps experiment with it a bit. How about a working group to explore some of Pravati’s ideas further?” Vera seems hesitantly accepting of the idea. She looks to Gerald, but he’s knee-deep in his inbox. She looks to Dave, who’s perked up since hearing the word ‘blockchain’. He’s nodding furiously.

“OK, Pravati could you have a look into this and then report back at our next meeting please?” says Vera. “Sure, I’d be happy to,” says Pravati, who’s been burned by Vera’s vague requests before. “I just need to ensure we’re agreed on some scope. I’d like to take a Wednesday afternoon to focus on this for the next three weeks, and pull in Keiko to double-check the technical side of things.”

“Alright, I’ll have to check with Keiko’s line manager, but that sounds fine,” says Vera. “Also, how would you like me to report back? In a report, with a slide deck, or something else?” asks Pravati. “Oh just some slides will be fine” says Vera.

As I argued in a paper I (self-)published with my thesis supervisor 11 years ago, if something is Vague, then according to the Oxford English Dictionary, it is “couched in general or indefinite terms” being “not definitely or precisely expressed”. In other words, as with the example of Vera above, the person expressing the idea doesn’t really know what they’re talking about.

When it comes to Generative ambiguity, the part of the continuum represented by Gerald, then an individual gives a name to a nebulous collection of thoughts and ideas. It might make some sense to them, given their own experiences, but it can’t really be conveyed well to others.

Creative ambiguity is where one aspect of a term is fixed, much in the way a plank of wood nailed to a wall would have 360-degrees of movement around a single point. Whilst a level of agreement can exist here, for example in the case of Chitundu talking about blockchain in a business context, it nevertheless remains highly contextual. It is dependent, to a great extent, upon what is left unsaid. A research project just on ‘blockchain’ in general would probably fail.

I would argue that Productive ambiguity is where real innovative work happens. This is the least ambiguous part of the continuum, an area in which more familiar types of ambiguity such as metaphor are used (either consciously or unconsciously) in definitions. The phrase “streamline our verification processes” in the example is productively ambiguous because it defines an area of enquiry without nailing it down too specifically.

Finally, we have Dead metaphors which happen when people want to remove all wiggle room from a term. Terms and the ideas behind them become formulaic and unproductive. They can, however, be resurrected through reformulation and redefinition. So when Dave in the story above talks in buzzwords he’s cribbed from his network without understanding what he means, he’s not really saying anything.

My reason for continually talking about ambiguity is that I believe there is a sweet spot in all areas of life. If an idea or concept being introducing doesn’t make sense to you, or if it makes sense only to you, then it needs more work. At the other end of the spectrum, if what’s being mentioned just feels clichéd and isn’t bringing any enlightenment, that’s no good either.

The interesting work happens when there’s an idea or concept that kind of makes sense to people with a similar backgrounds, experience, and/or interests. If it’s left there, though, it’s not useful enough. The idea or concept needs to be worked on further so that it can be applied more widely, so that others who don’t share that background, experience, or interest can see themselves in it.

I’d argue that this is what successful advertising and branding is. It’s how political slogans work. And, for the purposes of this post, it’s how things get done in a business setting.

When we’re doing new work, we tend to jump to conclusions and define things too quickly. This post outlines why that’s a bad idea, and what we can do to counteract these tendencies.

In his cheat sheet to cognitive biases, Buster Benson categorises the 200+ he identifies into three ‘conundrums’ that we all face:

One of the reasons that the Manifesto for Agile Software Development has been so impactful, even beyond the world of tech, is that it’s a form of granting permission. Instead of having to know everything up front and then embark on a small matter of programming, there is the recognition that meaning can accrete over time as systems develop.

It is therefore crucial to ensure that the project heads off on an appropriate trajectory. It’s also important that it can be nudged back on course should it stray from meeting the needs of users/participants/audience.

A tendency that I see with many innovation projects with which I’ve been involved is a lack of tolerance for ambiguity. By this I mean that because, as Benson notes, we never have enough time, “we jump to conclusions with what we have and move ahead”. In addition, because the world is a confusing place (especially when we’re doing new things!) “we filter lots of things out” and “create stories to make sense out of everything”.

It’s understandable that we do this, either consciously or unconsiously — and I’m certainly not immune from it! However, ever since studying ambiguity helped me with my doctoral thesis, I’ve been interested in how understanding different forms of ambiguity can help me in my work as a cooperator and consultant.

I’m going to discuss a Continuum of Ambiguity which I developed, based on the work of academics, and in particular Empson (1930), Robinson (1941) and Abbott (1997). I’m going to try and keep what follows as practical as possible, but for background reading you might find this article I wrote over a decade ago useful, or indeed Chapter 3 of my Essential Elements ebook, which is available here.

If we imagine ambiguity to be a continuum, then a lot of what happens with innovation projects happens at either end of the continuum. To the far left, things are left unhelpfully vague in a way that nobody really knows what’s going on. Anything and everything is up for grabs.

Alternatively, to the far right of the continuum, there’s a rush to nail everything down because this seems just like a project you’ve done before! Or there are massive time/cost pressures. Except of course, it isn’t just like that previous project, and by rushing you burn through even more time and money.

In my experience, what’s necessary is to sit with the ambiguity that every project entails: to understand what’s really going on, to look at things from many different angles, and ultimately, to shepherd the project into a part of the continuum I call ‘productive ambiguity’.

To define quickly the three parts of the Continuum of Ambiguity:

There was a time when ‘Uber for X’ was a popular way of getting funding. Without nailing down exactly what would happen or how it would work, the simplicity and game-changing approach that Uber took to booking a taxi could be applied to other areas or industries.

These days, ‘Uber for X’ is a dead metaphor as it’s been overused and is little better than a cliché. This is important to note, as an idea does not become (or remain) productively ambiguous without some work.

I’m working with the Bonfire team at the moment on the Zappa project. Unlike something such as Mastodon (“Twitter, but decentralised!”) or Pixelfed (“Instagram, but federated!”) the team hasn’t completely settled on a way of describing Bonfire which is productively ambiguous.

The tendency, which they are resisting nobly, is always to nail things down. Especially when you have funders. For example, it would be easy to decide in advance what is technically possible when attempting to counteract mis/disinformation in federated networks. Instead, because Bonfire is so flexible, they are sitting with the ambiguity and searching for use cases and metaphors which will help illuminate what might be useful.

One promising avenue, as well as doing the hard yards of user research and the synthesis of outputs this generates, is to use Marshall McLuhan’s notion of ‘tetrads’. The above example is taken from a post by Doc Searls in which he explicitly considers social media and what it improves, obsolesces, retrieves, and reverses.

There is no one framework or approach which can give the ‘truth’ of how a project should proceed, or what users want. Instead, by considering things from multiple angles, the overlap between desirable, technically possible, and needed by users comes into focus.

Instead of a conclusion, I will instead finish with an exhortation: sit with ambiguity! And while you’re sitting with it as a team, talk about it and resist the temptation to bring in dead metaphors. Instead of conceptualising the conversations you have about the project as “going round in circles” consider instead that it’s more likely that you are spiralling round an idea in an attempt to better understand and define it.

Given the news of the passing of Terry Jones, it seems appropriate to kick things off with one of my favourite parts of any Monty Python film:

Specifically:

ARTHUR: Who lives in that castle?

WOMAN: No one lives there.

ARTHUR: Then who is your lord?

WOMAN: We don’t have a lord.

ARTHUR: What?

DENNIS: I told you. We’re an anarcho-syndicalist commune. We take it in turns to act as a sort of executive officer for the week.

ARTHUR: Yes.

DENNIS: But all the decisions of that officer have to be ratified at a special biweekly meeting.

ARTHUR: Yes, I see.

DENNIS: By a simple majority in the case of purely internal affairs,–

ARTHUR: Be quiet!

DENNIS: –but by a two-thirds majority in the case of more–

ARTHUR: Be quiet! I order you to be quiet!

WOMAN: Order, eh — who does he think he is?

ARTHUR: I am your king!

WOMAN: Well, I didn’t vote for you.

ARTHUR: You don’t vote for kings.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail: Peasant Scene

Recently, I’ve become really interested in how decisions are made. Not personal decisions, such as “shall I change career?” or “who should I marry?”, but organisational decisions, such as “which project management tool should we use?” or “what should our strategy for the next three years be?”

As useful as they can be elsewhere in life, for this, things like The Decision Book don’t really cut it here. What we need is an approach or matrix; a way of deciding how, going into the situation, decisions are going to be made.

Related to this, I think, is the “default operating system” of hierarchy. I’ve cited elsewhere Richard D. Bartlett talking about the bad parts of hierarchy as being ultimately about what he calls “coercive power relationships”. In a hierarchy, people towards the bottom of the pyramid are being paid by the person (or people) at the top of the pyramid, so what they say, goes.

This means that, within a hierarchy, you’ve got a structure for the decision-making process, with power relationships between participants. And then, ultimately, however democratic the process purports to be, it’s ultimately the Highest Paid Person’s Opinion (HiPPO) that counts.

But what about in other situations, where the decision-making structure hasn’t been created? Who decides then?

For me, this isn’t an idle, theoretical question. I’ve seen the problems it can cause, especially around inaction. You can get so far by meeting up and having a big old discussion, but then how to you come to a binding decision? It’s tricky.

With non-hierarchical forms of organising, even getting into the decision-making process requires two things to happen first:

Let’s consider a fictional, but relatable, example. Imagine there’s a group of parents who have voluntarily decided to come together to raise money for their childrens’ sports team. They are not forming a company, non-profit, charity or any other form of organisation. They do not operate within a hierarchy. Nor have they decided how binding decisions can be made by the group.

Now let us imagine that this group of parents has to decide how best to raise money for the sports team. And once they’ve done that, they have to decide what to spend the money on. How do those decisions get made? What kinds of approaches work?

It is, of course, an absolute minefield, and perhaps why volunteering for these kind of roles seems to be on the decline. These situations can be particularly stressful without guidance or some kind of logical approach to non-hierarchical organising.

What has this got to do with ambiguity, and more specifically, the continuum of ambiguity shown above? I’d suggest that what is required in our fictional example is a way of organising that strikes a balance. In other words, one that that is Productively Ambiguous.

Hierarchies are a form of organising that can work well in many situations. For example, high-stakes situations, times when execution is more important than thought, and the military. For everything else, hierarchical organising can be a dead metaphor. It doesn’t represent how things are on the ground, and doesn’t allow any productive work to happen.

Imagine the situation if that volunteer group of parents decided to organise into a hierarchy. I should imagine they would spend more time thinking about and discussing power relationships and status than they would doing the work they’ve come together to achieve.

To the left of Productive Ambiguity lies creative ambiguity:

Whilst a level of consensus can exist within a given community within this Creative ambiguity part of the continuum, it nevertheless remains highly contextual. It is dependent, to a great extent, upon what is left unsaid – especially upon the unspoken assumptions about the “subsidiary complexities” that exist at the level of impression. The unknown element in the ambiguity (for example, time, area, or context) means that the term cannot ordinarily yet be operationalised within contexts other than communities who share prior understandings and unspoken assumptions.

Digital literacy, digital natives, and the continuum of ambiguity

Creative ambiguity relies on unspoken assumptions and previous tight bonds between people. This approach might work extremely well if, for example, the parents had themselves been part of a sports team together in their youth.

The chances are, however, that there would be at least a minority in the group who do not share this commonality. As a result, those unspoken assumptions would become a stumbling block and a barrier.

Far better, then, to focus on the area of productive ambiguity:

Terms within the Productive part of the ambiguity continuum have a stronger denotative element than in the Creative and Generative phases. Stability is achieved through alignment, often due to the pronouncement of an authoritative voice or outlet. This can take the form of a well-respected individual in a given field, government policy, or mass-media convergence on the meaning of a term. Such alignment allows a greater level of specificity, with rules, laws, formal processes and guidelines created as a result of the term’s operationalisation. Movement through the whole continuum is akin to a substance moving through the states of gas, liquid and solid. Generative ambiguity is akin to the ‘gaseous‘ phase, whilst Creative ambiguity is more of a ‘liquid‘ phase. The move to the ‘solid’ phase of Productive ambiguity comes through a process akin to a liquid ‘setting’.

Digital literacy, digital natives, and the continuum of ambiguity

Instead of hierarchy or unspoken assumptions, progress happens by following a path between over-specifying the approach, and allowing chaos to ensue.

In practice, this often happens by one or a small number of people exerting moral authority on the group. This occurs through, for example:

I have more to write on all of this at some point in the future, but I will leave it here for now. It’s interesting that this is at odds with the way that I see many attempts at decision-making happen – either inside or outside organisations…

In this week’s BBC Radio 4 programme Thinking Allowed, there’s an important part about ambiguity:

Laurie Taylor explores the origins and purpose of ‘Business Bullshit’, a term coined by Andre Spicer, Professor of Organizational Behaviour at Cass Business School, City University of London and the author of a new book looking at corporate jargon. Why are our organisations flooded with empty talk, injuncting us to “go forward” to lands of “deliverables,” stopping off on the “journey” to “drill down” into “best practice.”? How did this speech spread across the working landscape and what are its harmful consequences? They’re joined by Margaret Haffernan, an entrepreneur, writer and keynote speaker and by Jonathan Hopkin, Associate Professor of Comparative Politics at the LSE.

The particular part is the second section of the programme, in which Margaret Haffernan explains that organisations attempt (in vain) to eliminate ambiguity. As such, they play a constant game of inventing new terms and initiatives, which not only work no better than the previous ones, but serve to justify inflated salaries.

The episode is available online here.

One of my favourite things about the Web is the ease at which serendipity occurs. We take it for granted these days but occasionally wonderful things happen that make us rediscover the joy of connection.

I was browsing The Setup, a wonderful site that interviews people about the hardware and software they use. Being particularly interested in those using Linux (as I do these days) I was delighted to come across John MacFarlane’s interview.

MacFarlane is a Professor of Philosophy at UC Berkeley and his website details both his interests and academic papers. I was delighted to come across a paper entitled Vagueness as Indecision, which is available as a preprint download.

It’s been a while since I studied formal logic at university, but I managed to get by while reading this paper, especially as MacFarlane gives homely examples. He takes an expressivist position in taking the position that, “vagueness… is literally indecision about where to draw lines”.

On page seven, and quoting a character from Spiderman in passing, MacFarlane states:

In principle, I can use ‘that’ to refer to any object. But with this freedom comes great responsibility. I must provide my hearers with enough cues to enable them to associate my use of ‘this’ with the same object I do, or communication will fail. Sometimes this doesn’t require anything extra, because it is mutually known that one object is salient, so that it will be assumed to be the referent in the absence of cues to the contrary. Other times it requires pointing. And in some cases simply pointing isn’t enough. But in every case, we’re obliged to do whatever is required to get our hearers to associate the same object with the demonstrative that we do. If we fail to do this, it will be sheer luck if they understand us.

In my book, The Essential Elements of Digital Literacies I pointed out that productive discourse involves interaction at the overlap of the denotative and connotative aspects of a term or phrase:

What MacFarlane is pointing out is something similar, but outside the realm of ambiguity. For something to be ambiguous, it cannot be merely vague — although right on the left-hand boundary of that overlap is where the most vague ambiguous terms and phrases reside.

What MacFarlane is pointing out is something similar, but outside the realm of ambiguity. For something to be ambiguous, it cannot be merely vague — although right on the left-hand boundary of that overlap is where the most vague ambiguous terms and phrases reside.

Within that overlap resides the continuum of ambiguity:

In other words, just as ‘dead metaphors’ are to the right of Productive Ambiguity and occur when there’s denotation but little connotation, so ‘vagueness’ lies to the left of Generative Ambiguity and, as MacFarlane would put it, happens due to semantic indecision.

In other words, just as ‘dead metaphors’ are to the right of Productive Ambiguity and occur when there’s denotation but little connotation, so ‘vagueness’ lies to the left of Generative Ambiguity and, as MacFarlane would put it, happens due to semantic indecision.

The crux of MacFarlane’s position is that to have a meaningful interaction, two people have to agree where the ‘boundaries’ are to what they’re discussing:

Here is the upshot. While in using a bare demonstrative like ‘this,’ one must have a definite object in mind, and successful uptake requires recognizing what object that is, there are no analoguous requirements for the use of ‘large.’ The speaker need not have in mind a particular delineation (even a ‘fuzzy’ one), and the hearer need not associate the speaker’s use with a particular delineation. What we get instead are constraints on delineations. (p.11)

He continues, continuing his example of a trainee at an apple-sorting factory learning what a ‘large’ apple is:

Indecision is a practical state; it concerns plans and intentions, not belief. Just as one might plan to buy toothpaste, but not yet have settled on which toothpaste one will choose when confronted with a rack of them at the store, so one might have settled on counting apples greater than 84mm in diameter as large, without having settled on whether one would count a 78mm apple as large.

So for an interlocutor or reader to consider something ‘ambiguous’ they must ‘tolerate’ the semantic decisions made by the person with whom they’re interacting. If they don’t, then the lack delineation leads to vagueness.

I suggest, then, the ‘tolerance’ intuition can be explained as an awareness that a proposal to draw a sharp line in any particular place would be rejected for pragmatic reasons. Nothing about the meanings of vague words is inconsistent with drawing a sharp boundary; it’s just tha the cases in which a proposal to draw a sharp boundary would be sensible are few and unusual.

In other words, we humans are pretty good at getting by using heuristics. We agree to suspend disbelief (and therefore enter the continuum of ambiguity) to see whether doing so is, to use the words of William James ‘good in the way of belief’.

In conversation with Audrey Watters and Kin Lane yesterday, I managed to articulate something that’s been bothering me for a while. This is my attempt to record that so I can refer to it later.

I refer to the above diagram a lot on this blog, as it’s my way of thinking about this space. I’m not going to explain it in depth here so for those new to it, check out the slides from this seminar I did at MMU last year, or check out the chapter on ambiguities in my ebook.

Ambiguity is a relative term. For those who have shared touchstones (e.g. people who work in a given sector) terms can contain more of a connotative aspect. They get what’s going on without having it all spelled out for them. However, there are those new to a sector, and there are also those who, quite rightly, want to take ideas, processes, and terminology and use them in other sectors.

Collectively, we come up with processes to do things, or names for particular approaches, or perhaps even a term for a nebulous collection of practices. For example, ‘agile development’, or ‘human-centered design’, or ‘digital literacy’. These work for a while but then start to use their explanatory power as they move along the continuum of ambiguity. Eventually, they become ‘dead metaphors, or clichés.

In that conversation with Audrey and Kin yesterday, I described this in terms of the way that, eventually, we’re forced to rely on brand rather than processes.

Let me explain.

Take the term ‘agile development’ — which is often shortened to just ‘agile’. This is an approach to developing software which is demarcated more by a particular mindset than a set of rules about how that development should happen. It’s more about ‘agility’ than ‘agile’.

That, of course, is lost when you try and take that out of its original setting (amongst the people are using it to be creatively ambiguous). All sorts of things are said to be ‘agile’. I even heard of one person who was using ‘agile’ to mean simply ‘hotdesking’!

The problem is that people will, either purposely or naïvely, use human-invented terms in ‘incorrect’ ways. This can lead to exciting new avenues, but it also spells the eventual death of the original term as it loses all explanatory power. A dead metaphor, as Richard Rorty says, is only good as the ‘coral reef’ on which to build other terms.

It’s therefore impossible, as individuals and organisations, to rely on a particular process over the long-term. The meaning of the term you use to describe that process will be appropriated and change over time. This means that the only defensive maneuver is to rely on brand. That’s why, for example, people call in McKinsey to do their consulting for them, rather than subscribe to a particular process.

As ever, this isn’t something to bemoan, but something to notice and to take advantage of. If you come up with a name for a process or way of doing things that is successful, then you no longer have control over it. Yes, you could attempt to trademark it, but even this wouldn’t stop it from having a different meaning ‘out in the wild’.

Instead, be ready to define the essence of what is important in your approach. This can then be codified in many different ways. You’re still going to have to rely on your brand (personal/organisational) to push things forwards, but at least you can do so without trying to hang on to an initial way of framing and naming the thing.

Ontology is the philosophical study of the nature of being, becoming, existence or reality as well as the basic categories of being and their relations. Traditionally listed as a part of the major branch of philosophy known as metaphysics, ontology often deals with questions concerning what entities exist or may be said to exist and how such entities may be grouped, related within a hierarchy, and subdivided according to similarities and differences. (Wikipedia)

I’d argue that the attempt to define what ‘exists’ within a given system is usually a conservative, essentialist move. It’s often concerned with retro-fitting new things into the current status quo, a kind of Kuhnian attempt to save what might be termed ‘normal science’.

Perhaps my favourite example of this kind of post-hoc ontology is from a reference Jorge Luis Borges makes to a fictional taxonomy in a book he calls Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge:

On those remote pages it is written that animals are divided into (a) those that belong to the Emperor, (b) embalmed ones, (c) those that are trained, (d) suckling pigs, (e) mermaids, (f) fabulous ones, (g) stray dogs, (h) those that are included in this classification, (i) those that tremble as if they were mad, (j) innumerable ones, (k) those drawn with a very fine camel’s hair brush, (l) others, (m) those that have just broken a flower vase, (n) those that resemble flies from a distance.

This, of course, is meant to be humorous. Nevertheless, we’re in danger when a dominant group sees the current state of play as the ‘natural order of things’. It’s bad enough when this is latent, but even worse when essentialst worldviews are codified into laws — and by ‘law’ I’d include ‘code’.

The thing that disturbs me most is when people accept the artefacts that have been left for them as the given circumstances of nature… It’s this automatic acceptance of how things are that leads to a sense of helplessness about changing any of them. (Douglas Rushkoff)

This week, a survey was sent out to the Open Badges community on behalf of the Credential Transparency Initiative. This initiative is funded by the Lumina Foundation, an organisation that describes itself as an “independent, private foundation committed to increasing the proportion of Americans with degrees, certificates and other high-quality credentials to 60 percent by 2025.” The Lumina Foundation therefore has a vested interest in deciding what counts as a ‘high-quality credential’.

The problem is, of course, that what one well-funded, high-profile group decides after ‘consulting the community’ is likely to be adopted more widely. This is how de facto standards emerge. They may decide to play the numbers game and equate certain types of badges with degrees. Or, they may choose to go to the other end of the spectrum and ensure that badges do not equate with ‘high-quality’ credentials. Either way, it’s not really up to them to decide.

The survey featured this highly problematic question:

There are all kinds of assumptions baked into this question that need to be unpacked. For example, perhaps the biggest is that all of these have an ‘essence’ independent of one another, rather than in relation to each other. I see this as an attempt, either consciously or unconsciously, to turn the notion of a ‘badge’ into what Richard Rorty termed a ‘dead metaphor’:

Old metaphors are constantly dying off into literalness, and then serving as a platform and a foil for new metaphors. (Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, 16)

In my doctoral thesis (better consumed as this ebook), I used Rorty’s work along with that of William Empson to come up with a ‘continuum of ambiguity’:

The idea behind this continuum is that almost every term we use to describe ‘reality’ is metaphorical in some way. Terms we use to refer to things (e.g. ‘badge’) contain both denotative and connotative aspects meaning that the person using the term cannot be absolutely certain that the person they are communicating with will understand what they mean in the same way.

Image CC BY-ND Bryan Mathers

The more we try and create a one-to-one relationship between the utterance and the understanding of it, the more we are in danger of terms ‘falling off’ the continuum of ambiguity and becoming dead metaphors. They “lose vitality” and are “treated as counters within a social practice, employed correctly or incorrectly.” (Objectivity, Relativism, and Truth, 171). Such terms have the status of cliché.

The attempt to create a one-to-one relationship between a term as written or spoken, and the term as it is understood by an interlocutor or reader, is an understandable one. It would do away with the real, everyday problems we’re faced with when trying to understand the world from someone else’s point of view. As Rorty puts it, “the world does not provide us with any criterion to choose between alternative metaphors” (The Contingency of Language, 6). The problem is that if we have a single ontology, then we have a single worldview.

Returning to Open Badges, it would be difficult to do any interesting and useful work with the term if it becomes a dead metaphor. For example, I’m quite sure that there’s nothing many of those in Higher Education would like better than to demarcate what a badge ‘counts for’ and the situations in which it can be used. After all, organisations that have histories going back hundreds of years, and which are in the game of having a monopoly on ‘high-quality’ credentials need to protect their back. If they can create a dead metaphor-based ontology in which badges count as something much lower ‘quality’ (whatever that means) than the degrees they offer, then they can carry on as normal.

The fading conviction originating with Plato that language can adequately represent what there is in words opens the way for a pragmatic utilization of language as a means to address current needs through practical deliberations among thoughtful people. (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

At this point, I’m tempted to dive into differential ontology and the work of Derrida and Deleuze. Instead I’ll simply point out that the reductive attempt to define an essentialist ontology of credentials is doomed from the outset. What we need instead is to ensure that our use of terms such as ‘Open Badges’ are what I would call ‘productively ambiguous’ — that is to say, in the Pragmatist tradition, ‘good in the way of belief’.

Or, if you like your takeaways more pithy: Keep Badges Weird!