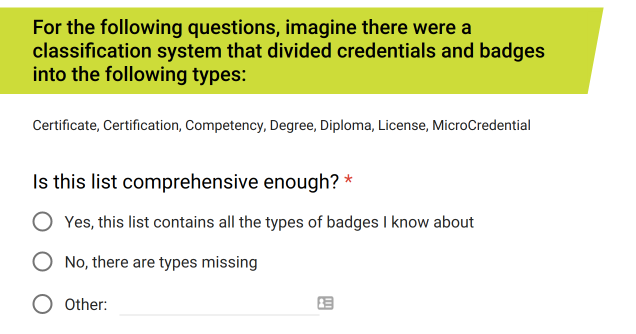

Imagine the situation: there’s a business meeting. I’ll leave it up to you as to whether this is an in-person meeting or a virtual one, but there are five people present:

- Vague Vera

- Generative Gerald

- Creative Chitundu

- Productive Parvati

- Dead Dave

These are all supposed to represent various parts of a continuum that I’ve used a lot on this blog. In fact, I’ve used this image in pretty much every post. However, what it doesn’t include is the area to the left of the continuum — thoughts, ideas, and utterances that are ‘vague’.

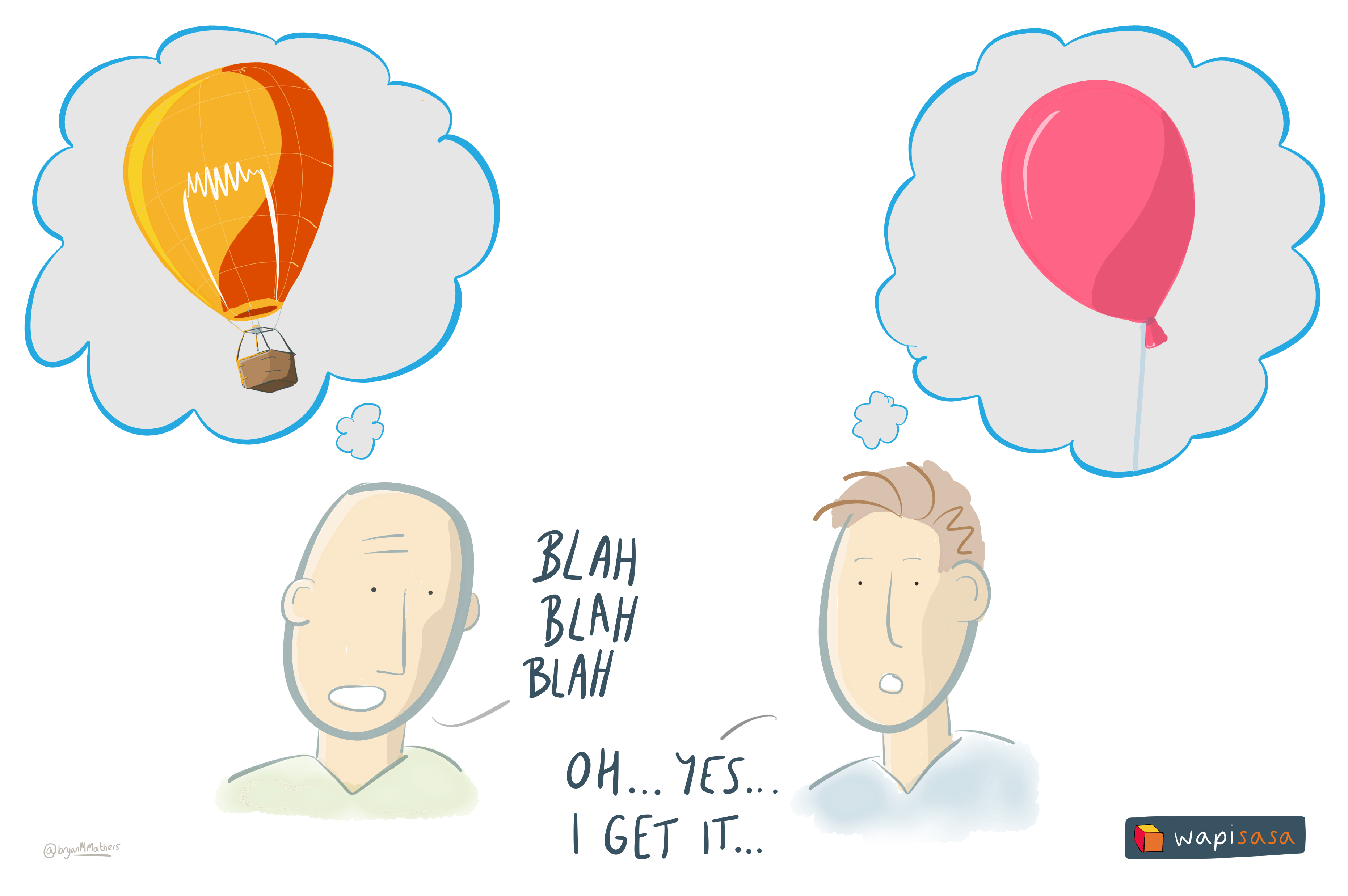

Back to the meeting, and Dave is speaking in clichés (aka ‘dead metaphors’) again. “What we need to do is synergise our verticals” he says. Parvati rolls her eyes; Dave’s been spending too much time on LinkedIn.

“Dave, I don’t think you understand our strategic business direction” says Vera. “We’re aiming to integrate new technologies to enable growth!” Everyone nods their heads, but no-one really understands what she means by this. “Have you got any ideas, Gerald?”

Looking uneasily around the room, Gerald utters a nervous little cough before saying, “well, I did have one idea, but I’m not sure if it’ll make much sense to you.” He looks out of the window, inhales deeply, and then spends the next few minutes outlining how he believes that web3 is like a cross between the Roman empire and freeform jazz. The rest of the meeting’s participants are utterly lost but try not to show it.

After a few awkward seconds of silence, Chitundu raises a finger and starts talking about a conference he went to recently. “At BizFest last year there was a speaker who was talking about the application of blockchain to verify core business processes,” he says. “What I liked about it was that he was really practical, but I can’t exactly remember what I thought we could use it for.”

Dave and Gerald are no longer concentrating and are instead checking their emails, but Vera chips in. “Yes, this is what I meant about integrating new technologies to enable growth!” Emboldened, Chitundu continues, “well you know how in the last annual report it showed we spend a lot of money on de-duplicating records? Perhaps we could use it for something to do with that?”

Suddenly, Pravati is drawing shapes connected with lines on a whiteboard. “Yes! She says, blockchain is basically a boring, back-office technology. So as long as we don’t store any sensitive data on there, we could use it to streamline our verification processes.” Vera’s eyes have glazed over slightly but she’s nodding.

Chitundu is excited. “I love this, and I think we should perhaps experiment with it a bit. How about a working group to explore some of Pravati’s ideas further?” Vera seems hesitantly accepting of the idea. She looks to Gerald, but he’s knee-deep in his inbox. She looks to Dave, who’s perked up since hearing the word ‘blockchain’. He’s nodding furiously.

“OK, Pravati could you have a look into this and then report back at our next meeting please?” says Vera. “Sure, I’d be happy to,” says Pravati, who’s been burned by Vera’s vague requests before. “I just need to ensure we’re agreed on some scope. I’d like to take a Wednesday afternoon to focus on this for the next three weeks, and pull in Keiko to double-check the technical side of things.”

“Alright, I’ll have to check with Keiko’s line manager, but that sounds fine,” says Vera. “Also, how would you like me to report back? In a report, with a slide deck, or something else?” asks Pravati. “Oh just some slides will be fine” says Vera.

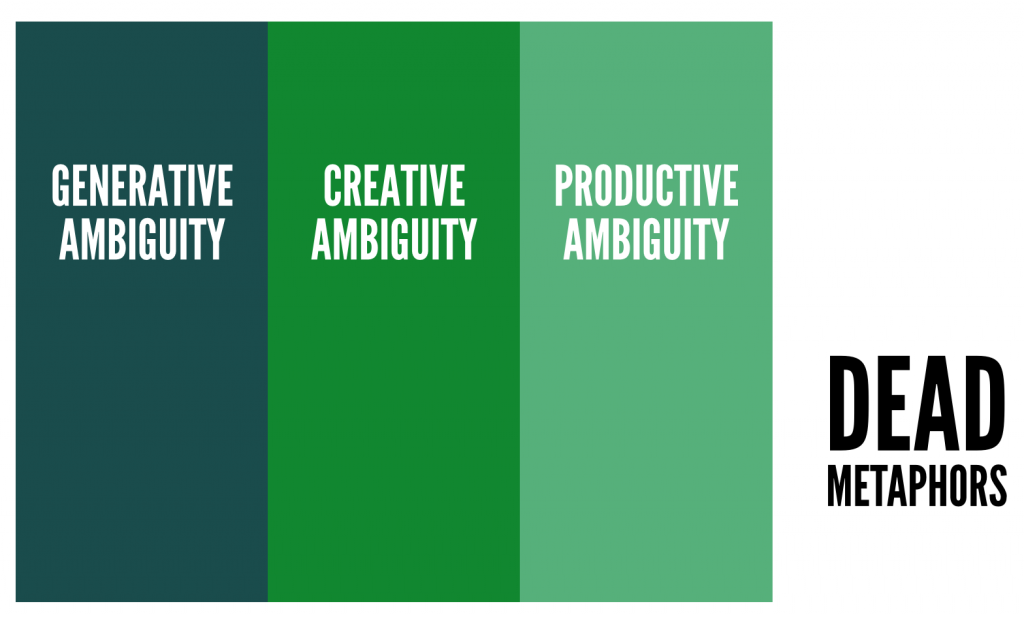

As I argued in a paper I (self-)published with my thesis supervisor 11 years ago, if something is Vague, then according to the Oxford English Dictionary, it is “couched in general or indefinite terms” being “not definitely or precisely expressed”. In other words, as with the example of Vera above, the person expressing the idea doesn’t really know what they’re talking about.

When it comes to Generative ambiguity, the part of the continuum represented by Gerald, then an individual gives a name to a nebulous collection of thoughts and ideas. It might make some sense to them, given their own experiences, but it can’t really be conveyed well to others.

Creative ambiguity is where one aspect of a term is fixed, much in the way a plank of wood nailed to a wall would have 360-degrees of movement around a single point. Whilst a level of agreement can exist here, for example in the case of Chitundu talking about blockchain in a business context, it nevertheless remains highly contextual. It is dependent, to a great extent, upon what is left unsaid. A research project just on ‘blockchain’ in general would probably fail.

I would argue that Productive ambiguity is where real innovative work happens. This is the least ambiguous part of the continuum, an area in which more familiar types of ambiguity such as metaphor are used (either consciously or unconsciously) in definitions. The phrase “streamline our verification processes” in the example is productively ambiguous because it defines an area of enquiry without nailing it down too specifically.

Finally, we have Dead metaphors which happen when people want to remove all wiggle room from a term. Terms and the ideas behind them become formulaic and unproductive. They can, however, be resurrected through reformulation and redefinition. So when Dave in the story above talks in buzzwords he’s cribbed from his network without understanding what he means, he’s not really saying anything.

My reason for continually talking about ambiguity is that I believe there is a sweet spot in all areas of life. If an idea or concept being introducing doesn’t make sense to you, or if it makes sense only to you, then it needs more work. At the other end of the spectrum, if what’s being mentioned just feels clichéd and isn’t bringing any enlightenment, that’s no good either.

The interesting work happens when there’s an idea or concept that kind of makes sense to people with a similar backgrounds, experience, and/or interests. If it’s left there, though, it’s not useful enough. The idea or concept needs to be worked on further so that it can be applied more widely, so that others who don’t share that background, experience, or interest can see themselves in it.

I’d argue that this is what successful advertising and branding is. It’s how political slogans work. And, for the purposes of this post, it’s how things get done in a business setting.