Ambiguity can often be caused through intentional or intentional use of zeugma and syllepsis:

In rhetoric, zeugma (/ˈzjuːɡmə/ (listen); from the Ancient Greek ζεῦγμα, zeûgma, lit. “a yoking together”[1]) and syllepsis (/sɪˈlɛpsɪs/; from the Ancient Greek σύλληψις, sullēpsis, lit. “a taking together”) are figures of speech in which a single phrase or word joins different parts of a sentence.

In my doctoral thesis, I noted that the words ‘digital’ and ‘literacy’ were combined to produce different kinds of ambiguity:

Zeugmas are figures of speech that join two or more parts of a sentence into a single noun, such as ‘digital literacy’. It is unclear here whether the emphasis is upon the ‘digital’ (and therefore an example of a prozeugma) or upon the ‘literacy’ (and therefore a hypozeugma). Which is the adjective?

Once you’ve spotted your first zeugma, you see them everywhere. They can be used to enlighten but also to deceive. I’m often a fan: terms where two words are ‘yoked together’ can be incredibly productive, leading to breakthroughs in groups that would otherwise be directionless.

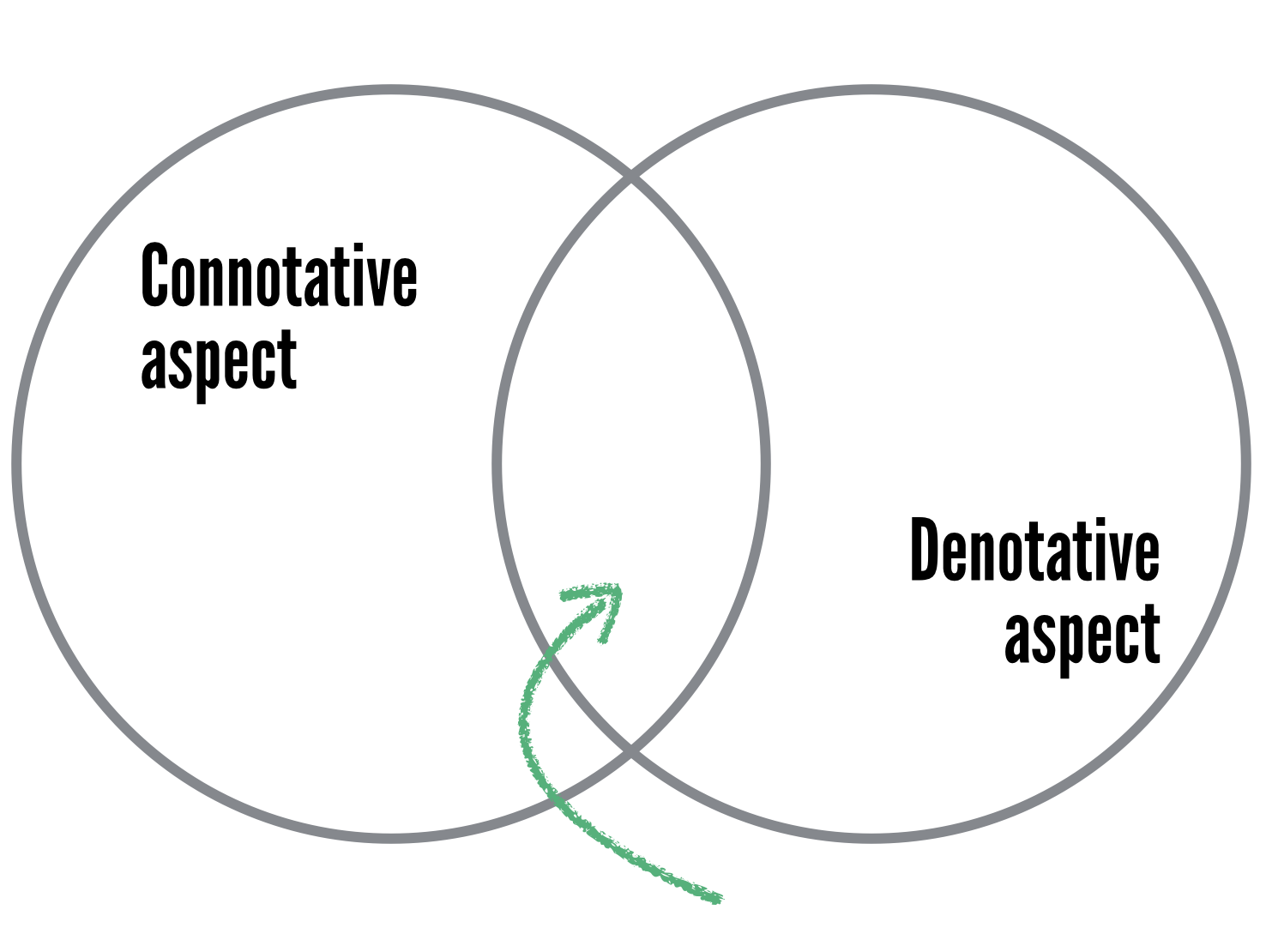

The way this approach works is to play around with the boundary of what something denotes (i.e. represents) and what it connotes (i.e. implies).

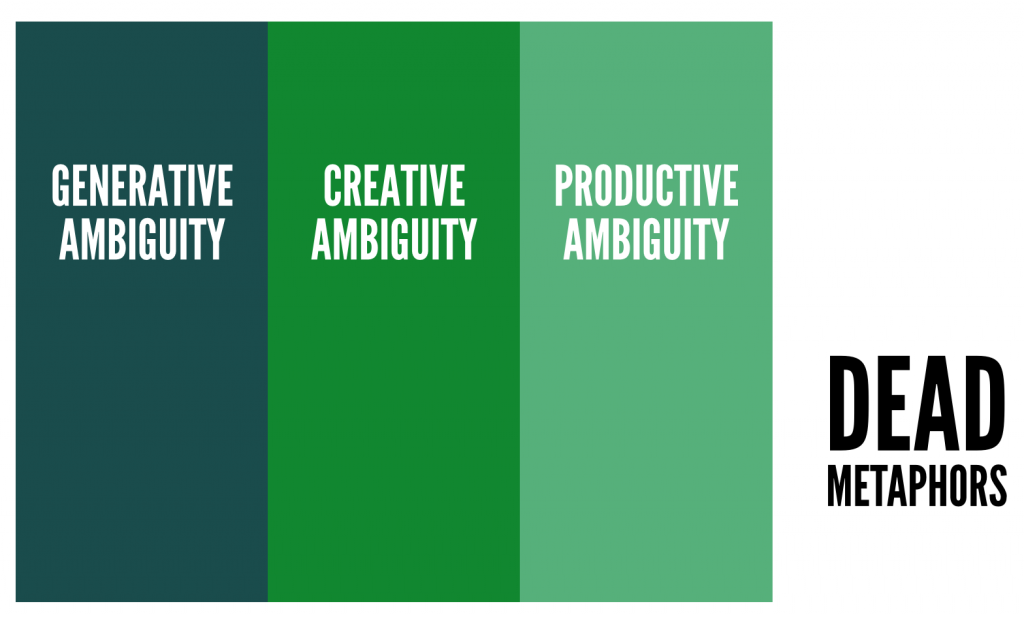

Within this overlap are different types of ambiguity, which I usually represent with the continuum of ambiguity (below). This is explained in more detail within a paper I wrote with my thesis supervisor, but broadly speaking:

- Generative ambiguity — works for you

- Creative ambiguity — works for people like you with domain knowledge

- Productive ambiguity — works for most people

- Dead metaphor — cliché with no power

What’s interesting in my work is that I get to collaborate with quite a few different organisations, either as clients or as sister organisations working towards a shared goal.

There have been some interesting zeugmas that arise and do some important work at the level of Creative Ambiguity and Productive Ambiguity. For example: Cooperative Technologists [CoTech] where it’s often unclear as to whether we’re cooperative technologists or cooperative technologists. Is the emphasis on the former or the latter?

My experience is that while zeugmas open up space for productive discussion and action, the terms themselves are usually on a journey. They may move in a linear way from Generative through Creative, to Productive Ambiguity before becoming a Dead Metaphor. But more often, they oscillate between Creative Ambiguity and Productive Ambiguity, with the terms being reinvigorated every so often with new insights and impetus.

In general, this post on a oft-neglected blog is mostly a reminder to myself to be aware of the power of ambiguity within my own work and of the different forms it can take.

Vagueness is, of course, always to be avoided (and sits to the left of Generative Ambiguity) but it’s actually quite a rare thing in my world.